# Load required libraries

library(tidyverse) # Data manipulation and visualisation

library(sf) # Simple features for spatial data

library(stats19) # Package for road crash data

library(tmap) # Thematic mappingSession 6: Joins, models and publishing your work

1 Introduction

By “publishing” in this context, we primarily mean submitting your project for assessment. However, the skills you learn here apply to various forms of publication:

- Reports (similar to the documents created in this module)

- Academic papers for journals or conferences

- Presentations (which can be created with Quarto using

format: revealjs) - Web applications or interactive dashboards

- Blog posts or technical documentation

The key principle is that good data science work should be reproducible, well-documented, and clearly communicated. This session will help you develop those skills.

In this session, we will explore techniques for joining, combining and aggregating datasets in R, particularly for spatial data. We’ll work with road crash data (STATS19), Lower Super Output Area (LSOA) boundaries, and census population data for West Yorkshire. Through this session, you’ll learn:

- How to perform spatial joins between point and polygon data

- How to join tables using common identifiers (key-based joins)

- How to calculate and visualize derived metrics from joined datasets

- How to create professional-looking reports with Quarto

The skills developed in this session are essential for transport data scientists who often need to combine data from various sources to gain comprehensive insights.

1.1 Required libraries

First, let’s load the libraries we’ll need for this session:

2 Data acquisition and preparation

2.1 Downloading STATS19 crash data

We’ll begin by downloading road crash data for four years (2019-2022) using the stats19 package:

# Download STATS19 crash data for 2019-2023

# We're downloading data for multiple years to have a robust dataset

crashes_2019 = get_stats19(year = 2019, type = "accidents", ask = FALSE)

crashes_2020 = get_stats19(year = 2020, type = "accidents", ask = FALSE)

crashes_2021 = get_stats19(year = 2021, type = "accidents", ask = FALSE)

crashes_2022 = get_stats19(year = 2022, type = "accidents", ask = FALSE)

crashes_2023 = get_stats19(year = 2023, type = "accidents", ask = FALSE)The get_stats19() function downloads the crash data. The parameters used are:

year: Specifies which year’s data to downloadtype: Selects the type of data (accidents, vehicles, or casualties)ask = FALSE: Automatically downloads without prompting for confirmation

2.2 Combining multiple years of data

Once we have the individual year datasets, we can combine them into a single dataframe using bind_rows():

# Combine all years into one dataset

# This creates a unified dataset for analysis across the full time period

crashes = bind_rows(crashes_2019, crashes_2020, crashes_2021, crashes_2022, crashes_2023)

# Let's check the dimensions of our combined dataset

dim(crashes)bind_rows() from dplyr appends the rows from each dataset, creating a unified dataset spanning all four years.

bind_rows() vs rbind() in R (click to expand)

Both bind_rows() and rbind() combine data frames row-wise, but they differ in behaviour and flexibility.

rbind() (Base R)

- Comes from base R

- Requires exactly matching column names and types

- Will throw an error if the data frames don’t align perfectly

df1 = data.frame(a = 1:2, b = c("x", "y"))

df2 = data.frame(a = 3:4, b = c("z", "w"))

rbind(df1, df2) # ✅ Worksdf3 = data.frame(a = 5:6, c = c("a", "b"))

rbind(df1, df3) # ❌ Error: column names do not matchbind_rows() (from dplyr)

- Part of the tidyverse

- More flexible than

rbind() - Automatically fills in missing columns with NAs

library(dplyr)

df1 = data.frame(a = 1:2, b = c("x", "y"))

df3 = data.frame(a = 5:6, c = c("a", "b"))

bind_rows(df1, df3) # ✅ Works, fills missing columns with NASummary Comparison

| Feature | rbind() |

bind_rows() |

|---|---|---|

| From | Base R | dplyr (tidyverse) |

| Requires same cols? | ✅ Yes | ❌ No |

| Fills missing cols | ❌ Error | ✅ With NA |

| Ideal use case | Controlled data | Flexible data wrangling |

Tip

- Use

rbind()if you’re sure the data frames have identical structure. - Use

bind_rows()for robust and flexible row-binding, especially in pipelines.

2.3 Converting crash data to sf object

To enable spatial operations, we need to convert our crash data into an sf (simple features) object:

# Creating geographic crash data

# This converts the data frame into a spatial object with point geometries

crashes_sf = format_sf(crashes)

head(crashes_sf)The format_sf() function from the stats19 package converts the crash coordinates into a spatial object. The note you see indicates that rows with missing coordinate values are automatically removed, as spatial objects cannot have NA values for coordinates/geometry.

2.4 Filtering for West Yorkshire

We’ll now filter the crash data to include only incidents that occurred within the West Yorkshire police force area:

# Filter crashes to only those that occurred in West Yorkshire

crashes_wy = crashes_sf |> filter(police_force == "West Yorkshire")

# Compare the number of rows before and after filtering

# This shows how many crashes occurred in West Yorkshire vs. the whole dataset

nrow(crashes_sf)

nrow(crashes_wy)3 Spatial joins

3.1 What is a spatial join?

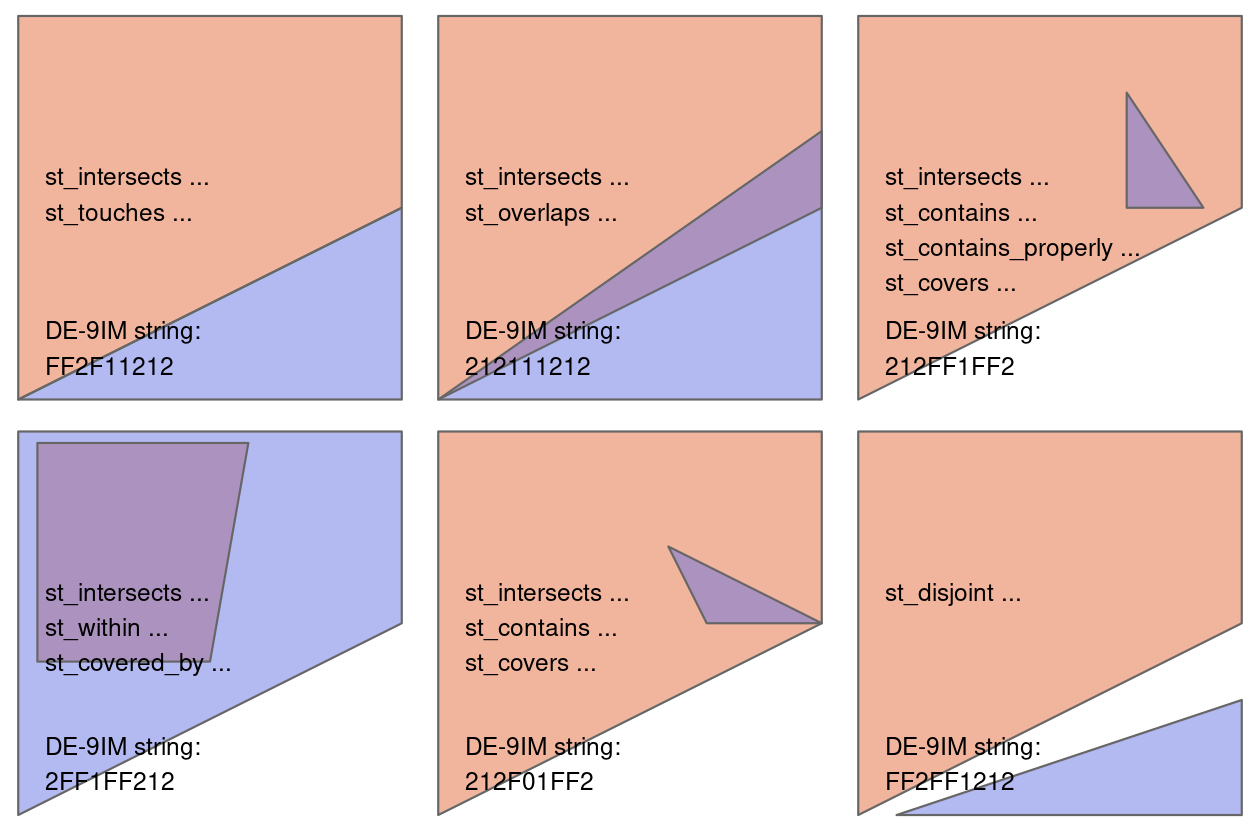

A spatial join combines two spatial datasets based on their geographic relationship — e.g., whether one geometry intersects, contains, or is within another.

In R, we use the sf package to handle spatial joins with functions like:

st_join(x, y, join = st_intersects)x: the primary spatial object (e.g. point or line data)y: the reference spatial object (e.g. polygons)st_intersects,st_within,st_contains, etc. define the spatial relationship

Why is it useful in transport data science?

Spatial joins are essential tools in transport data science for:

- Mapping transport observations (e.g. crashes, stops, GPS traces) to zones or regions

- Enriching data with attributes from other layers (e.g. population, accessibility, land use)

- Aggregating or summarising transport data by spatial units

They allow you to combine spatially referenced datasets in meaningful ways to gain insights and build models. We’ll use this technique to identify which LSOA each crash occurred in.

3.2 Loading LSOA boundary data

First, we load the LSOA (Lower Super Output Area) boundaries for West Yorkshire:

# Load the 2021 LSOA boundary data for West Yorkshire

lsoa_wy = read_sf("https://github.com/itsleeds/tds/releases/download/2025/p6-lsoa_boundary_wy.geojson")

# Retain only useful variables: LSOA code (lsoa21cd) and LSOA name (lsoa21nm)

lsoa_wy = lsoa_wy |> select(lsoa21cd, lsoa21nm)

# Check the structure of the data to understand what we're working with

glimpse(lsoa_wy)

# How many LSOAs are in our dataset?

# The cat() function in R is short for “concatenate and print”

cat("Number of LSOAs in West Yorkshire:", nrow(lsoa_wy))LSOAs are small geographic areas in the UK designed for reporting census and other neighborhood statistics. Each LSOA typically contains 400-1,200 households, and usually have a resident population of 1,000-3,000 people. We’re using the 2021 LSOA boundaries, which align with the most recent UK Census.

3.3 Performing a Spatial Join

Now we’ll perform a spatial join to determine which LSOA each crash occurred in:

# Perform spatial join to determine which LSOA each crash occurred in

# This adds LSOA information to each crash point

crashes_in_lsoa = st_join(lsoa_wy, crashes_wy)

# Check which columns were added from the LSOA dataset

# setdiff finds column names that are new in crashes_in_lsoa

added_columns = setdiff(colnames(crashes_in_lsoa), colnames(crashes_wy))

# The collapse argument is used in the paste() function,

# and it controls how to combine multiple elements into a single string.

# Here we add ", " between elements

cat("Columns added from LSOA data:", paste(added_columns, collapse=", "),"\n")

# Check if any crashes couldn't be assigned to an LSOA

na_lsoa = sum(is.na(crashes_in_lsoa$lsoa21cd))

cat("Number of crashes not matching any LSOA:", na_lsoa)The st_join() function links each crash point to the LSOA polygon that contains it. By default, it performs a “within” operation, checking if each point in the first dataset falls within any polygon in the second dataset. After this operation, each crash record will have additional columns from the LSOA dataset, including the LSOA code and name.

We use the setdiff() function to find column names that are new in crashes_in_lsoa — i.e., the ones that come from lsoa_wy.

3.4 Aggregating Crashes by LSOA

Next, we’ll aggregate the crash data to count how many crashes of each severity occurred in each LSOA:

# Aggregate crash data by LSOA, counting crashes of each severity

lsoa_crashes_count = crashes_in_lsoa |>

# Remove geometry column as we only need tabular data for aggregation

st_drop_geometry() |>

# Group by LSOA identifiers

group_by(lsoa21cd) |>

# Count crashes by severity level

summarise(

fatal_crashes_n = sum(accident_severity == "Fatal"), # Number of fatal crashes

serious_crashes_n = sum(accident_severity == "Serious"), # Number of serious crashes

slight_crashes_n = sum(accident_severity == "Slight"), # Number of slight crashes

all_crashes_n = fatal_crashes_n + serious_crashes_n + slight_crashes_n # Total number of crashes

)

# Display the first few rows of the aggregated data

head(lsoa_crashes_count)4 Key-Based Joins

In addition to spatial joins, we often need to join datasets based on common identifiers or keys. This is particularly useful for combining spatial data with non-spatial attributes.

The dplyr package provides a family of intuitive join functions:

| Join Type | Function | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Inner Join | inner_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps only matching rows in both datasets. |

| Left Join | left_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps all rows from df1, adds matching rows from df2. |

| Right Join | right_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps all rows from df2, adds matching rows from df1. |

| Full Join | full_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps all rows from both datasets. |

| Semi Join | semi_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps rows from df1 that have matches in df2. |

| Anti Join | anti_join(df1, df2, by = "key") |

Keeps rows from df1 that do not have matches in df2. |

4.1 Joining aggregated crash count data to LSOA Boundaries

Now we’ll join the aggregated crash counts back to the LSOA boundary data:

# Join crash count data back to LSOA boundaries

# This preserves the spatial information while adding the crash statistics

lsoa_crashes_wy = lsoa_wy |>

left_join(lsoa_crashes_count, by = "lsoa21cd")

# Check the columns in our joined dataset

colnames(lsoa_crashes_wy)

# Replace NA values with 0 for LSOAs that had no crashes

lsoa_crashes_wy = lsoa_crashes_wy |>

mutate(across(c(all_crashes_n, fatal_crashes_n, serious_crashes_n, slight_crashes_n),

~replace_na(., 0)))

# Count how many LSOAs had zero crashes

zero_crash_lsoas = sum(lsoa_crashes_wy$all_crashes_n == 0)

cat("Number of LSOAs with zero recorded crashes:", zero_crash_lsoas, "\n")

cat("Percentage of LSOAs with zero crashes:", round((zero_crash_lsoas/nrow(lsoa_crashes_wy))*100, 2), "%\n")We use left_join() to preserve all LSOAs, even those with no crashes. The by parameter specifies the columns to use for matching rows between the datasets. After this join, we have the spatial boundaries with the crash counts attached.

We also replace NA values with 0 for LSOAs that had no crashes, and calculate how many LSOAs had zero crashes recorded.

Question: What happens if you use right_join() instead?

4.2 Loading census population data

We’ll now load census population data for the LSOAs, the census data is obtained from nomis, specifically the Number of usual residents in households and communal establishments in each LSOA. The data has been further cleaned for better processing.

# Load 2021 Census population data for LSOAs

pop_lsoa = read_csv("https://github.com/itsleeds/tds/releases/download/2025/p6-census2021_lsoa_pop.csv")

# Display the first few rows

head(pop_lsoa)

# Basic summary statistics of the population data

summary(pop_lsoa$pop)This dataset contains population figures from the 2021 UK Census for each LSOA in England and Wales.

4.3 Joining population data

Next, we’ll join the population data to our LSOA crash data using the LSOA codes and names as keys:

# Join population data to our LSOA crash data

lsoa_crashes_wy = lsoa_crashes_wy |>

left_join(pop_lsoa, by = c("lsoa21cd", "lsoa21nm"))

# Check the first few rows of our joined dataset

head(lsoa_crashes_wy)

# Check if we have any missing population values after the join

missing_pop = sum(is.na(lsoa_crashes_wy$pop))

cat("Number of LSOAs with missing population data:", missing_pop, "\n")This operation adds the population data to our existing dataset, allowing us to calculate per-capita crash rates.

5 Creating new metrics

With our datasets joined, we can now create (mutate()) new metrics that provide more insight than the raw counts.

5.1 Calculating Crashes Per Person

We’ll calculate the number of crashes per person for each LSOA:

# Calculate crashes per person for each LSOA

lsoa_crashes_wy = lsoa_crashes_wy |>

mutate(

# Crashes per person (raw rate)

crash_pp = all_crashes_n/pop,

# Crashes per 1000 people (more intuitive scale)

crash_per_1000 = crash_pp * 1000,

# Proportion of crashes that were fatal or serious

severity_ratio = (fatal_crashes_n + serious_crashes_n) / all_crashes_n

)

# Replace NaN values in severity_ratio (from dividing by zero)

lsoa_crashes_wy$severity_ratio[is.nan(lsoa_crashes_wy$severity_ratio)] = 0

# Summary statistics of our derived metrics

summary(lsoa_crashes_wy$crash_pp)

summary(lsoa_crashes_wy$crash_per_1000)

summary(lsoa_crashes_wy$severity_ratio)These derived metrics normalize the crash counts by population, allowing for more meaningful comparisons between areas with different population sizes. Areas with higher values have more crashes relative to their population.

6 Visualisation

Finally, let’s visualise our results using the tmap package:

# Set tmap mode to static plotting

tmap_mode("plot")

# Create a more intuitive map showing crashes per 1000 people

map_crashes_per_1000 = tm_shape(lsoa_crashes_wy) +

tm_polygons(col = "crash_per_1000",

title = "Crashes per 1000 People",

palette = "Reds",

border.alpha = 0.3) +

tm_layout(title = "Road Crash Rates in West Yorkshire (2019-2023)",

title.size = 0.9,

title.fontface = "bold",

legend.position = c("right", "center"),

legend.text.size = 0.6,

legend.title.size = 0.8,

legend.outside = TRUE,

legend.outside.position = "right",

inner.margins = c(0.02,0.02,0.1, 0.4), # bottom,left,top,right

outer.margins = c(0.02, 0.02, 0.02, 0.02))

# Display the map

map_crashes_per_1000

# Create a map showing the severity ratio

map_severity = tm_shape(lsoa_crashes_wy) +

tm_polygons(col = "severity_ratio",

title = "Proportion of \nFatal/Serious Crashes",

palette = "Purples",

border.alpha = 0.3) +

tm_layout(title = "Crash Severity in West Yorkshire (2019-2023)",

title.size = 0.9,

title.fontface = "bold",

legend.position = c("right", "center"),

legend.text.size = 0.6,

legend.title.size = 0.8,

legend.outside = TRUE,

legend.outside.position = "right",

inner.margins = c(0.02,0.02,0.1, 0.5), # bottom,left,top,right

outer.margins = c(0.02, 0.02, 0.02, 0.02))

# Display the map

map_severityThese maps create choropleth visualizations where: - Each LSOA is colored according to its crash rate or severity ratio - The color palettes use darker colors to indicate higher values

7 Publishing your work with Quarto

Now that you’ve learned how to analyze and visualize transport data, let’s focus on how to present your work professionally for assessment or publication.

7.1 Citations and references

Properly citing sources is crucial for academic work and professional reports. Quarto makes this easy with built-in citation support.

7.1.1 Adding citations

To cite a source, use the @ symbol followed by the citation key from your .bib file:

Recent research shows that cycling infrastructure reduces casualty rates [@lovelace_stats19_2019].

You can also use multiple citations [@lovelace_stats19_2019; @morgan_2020].

For in-text citations with the author's name, use: As shown by @lovelace_stats19_2019, ...7.1.2 Managing your bibliography

Create a

.bibfile (e.g.,references.bib) with your referencesAdd it to your YAML header:

--- title: "My Transport Analysis" bibliography: references.bib ---Citations will automatically appear in your document with a References section at the end

You can find citation keys from Google Scholar, Zotero, or other reference managers.

7.2 Cross-references for figures and tables

Cross-references allow you to refer to figures, tables, and sections by number, which automatically updates if you reorganize your document.

7.2.1 Figure cross-references

```{r}

#| label: fig-crash-map

#| fig-cap: "Distribution of road crashes in West Yorkshire"

# Your plotting code here

tm_shape(crashes_sf) + tm_dots()

```

As shown in @fig-crash-map, crashes are concentrated in urban areas.7.2.2 Table cross-references

```{r}

#| label: tbl-crash-summary

#| tbl-cap: "Summary statistics for road crashes"

crash_summary |>

knitr::kable()

```

@tbl-crash-summary presents the key statistics.7.2.3 Section cross-references

# Introduction {#sec-intro}

See @sec-intro for background information.7.3 Making your reports look professional

7.3.1 Choosing output formats

Quarto supports multiple output formats. Specify in your YAML header:

---

title: "My Report"

format:

html:

theme: cosmo

toc: true

number-sections: true

pdf:

documentclass: article

revealjs: # For presentations

theme: dark

---7.3.2 Formatting tips

Code chunk options control how code appears:

```{r}

#| echo: false # Hide code, show only output

#| warning: false # Suppress warnings

#| message: false # Suppress messages

#| fig-width: 8 # Set figure width

#| fig-height: 6 # Set figure height

# Your code here

```Callout blocks highlight important information:

:::{.callout-note}

This analysis uses STATS19 data from 2019-2023.

:::

:::{.callout-warning}

Data completeness varies by year and region.

:::

:::{.callout-tip}

Consider using interactive maps for web outputs.

:::Tables can be formatted nicely with knitr::kable() or the gt package:

library(knitr)

crash_summary |>

knitr::kable(

caption = "Crash statistics by severity",

digits = 2,

format.args = list(big.mark = ",")

)7.3.3 Document structure

A well-organized report should include:

- Title and metadata (author, date, affiliation)

- Abstract or Executive Summary (brief overview)

- Introduction (context and objectives)

- Methods (data sources, analysis techniques)

- Results (findings with figures and tables)

- Discussion (interpretation and implications)

- Conclusion (summary and recommendations)

- References (automatically generated by Quarto)

7.3.4 Tips for submission

- Use version control: Commit your work regularly with Git

- Check your output: Always render your document before submission to catch errors

- Follow formatting guidelines: Check if there are specific requirements (word count, citation style, etc.)

- Include reproducible code: Make sure others can run your analysis

- Proofread carefully: Check for typos, broken links, and missing figures